After earning her freedom she began farming. She bought two black slaves to help her with the work. She later freed both men and married the man named Banneka, who said he had been a tribal prince in Africa before he was captured and sold into slavery. They continued to farm and raised four daughters. One of them, Mary, would later become the mother of Benjamin Banneker.

Mary married a freed African man and they also became tobacco farmers. Benjamin spent a lot of time with his grandmother Molly. She taught him to read and by the time he was five years old he could read from the Old and New Testaments. He was a whiz at math. When he was six he was helping the neighbors with their bookkeeping. He had a photographic* memory and could recall things in detail.

His father bought a 100-acre farm using 7,000 pounds of tobacco to pay for it. The tobacco farmers would receive a paper for the tobacco they sold and that paper could be used as money. He registered the farm, known as "Stout" in his name and also in the name of six-year-old Benjamin. At his father's death the farm would go directly to Benjamin since he was a co-owner.

They built a log cabin on the farm. Benjamin had to work hard and had little time to study. However, when he was nine years old he was able to go to a Quaker school for a couple of years, but there was to be no more schooling after that. He borrowed books and continued to study and learn on his own. He studied the stars and observed nature.

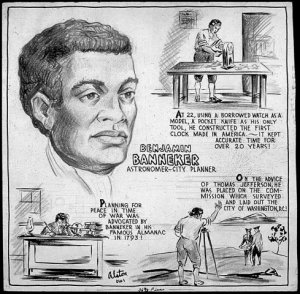

He was curious about time. Once he had an opportunity to borrow a pocket watch. Of course, he couldn't take it apart to see how it worked, but he studied it intently. He memorized every part of it and remembered where each part was in relation to the other parts. Then, amazingly, he carved the different parts from wood, making them larger and constructed a clock. His clock ran for years and kept accurate time. It also had a bell which rang on the hour. The word spread and many people came to his cabin to see his clock and to talk with him.

In addition to growing tobacco Benjamin had bee hives and raised a garden. He spent hours watching the bees and learning their habits.

When he was 32 years old he bought his first book, a used Bible. He enjoyed music and played the violin and flute. He never married so for years he led a lonely life.

In 1771 two Quaker brothers, John and Andrew Ellicott came to the area. The Ellicott family bought a lot of land and built automated grist* mills to grind grain into flour. With the mills nearby, the farmers could now grow corn and wheat and not have to depend on the tobacco crop to make a living. Growing tobacco year after year depleted the soil and after a while the crops did not grow well.

It took a lot of workers to build the grist mills and Benjamin and his mother delivered food to be cooked. The brothers built a store, and a town flourished in the area.

The colonies gained their independence from England, but the slaves were still in bondage. Benjamin's neighbors didn't want their slaves to have contact with him lest they become discontented with their lot and decide they too, would like to be free.

In 1766 Benjamin inherited property from his great-grandfather in Ireland. It was a large estate. He went to Ireland and sold it for a large sum of money and returned to Pennsylvania a very rich man.

Benjamin became good friends with one of the Ellicott sons. He was much younger than Benjamin, but they shared a common interest in astronomy and science. George Ellicott had a telescope which he loaned to Benjamin along with instruments and books about astronomy. The study of astronomy consumed him and he neglected his fields and animals to study. Through mathematical calculations he was able to predict when there would be an eclipse of the sun.

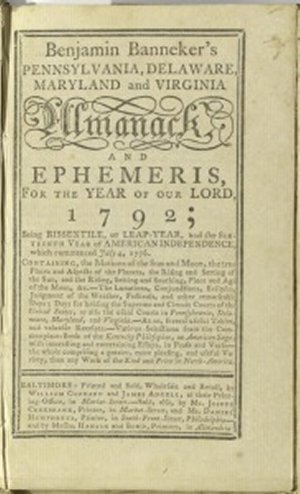

Many almanacs* were produced at that time and Benjamin decided he would write his own farmer's almanac. His almanac would show the position of the sun and planets for each day of the coming year. He included information for farmers to use to aid them in the planting and harvesting of their crops.

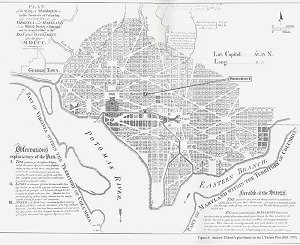

Before he finished his almanac he had to put the project on hold. The U.S. Government was going to build a Capital City. George Washington chose the site and asked Andrew Ellicott to survey the land. Ellicott could choose his own staff. His brother suggested Banneker, who was now 60 years old.

Banneker's knowledge of astronomy and locating positions on land was vital to the survey. In modern times with satellites in the sky people use global positioning (GPS)* to do such things, but when the team was planning the survey for the Capital, such technology did not exist. Banneker's job was to take care of the astronomical clock. He would watch the stars through the telescope at night and sleep in the afternoon.

Banneker and Ellicott rode to Virginia to the base camp on horseback. The work started. Banneker supplied the astronomical expertise. After a couple of months the boundaries were marked and he went home.

A Frenchman, Pierre Charles L'Enfant (lawn-fawnt) was appointed to work with the surveyors. He would draw the plans for the city, but he did not get along with the others and he did not see the plan to completion.

According to legend Banneker had seen the plans and helped to reproduce them from memory after L'Enfant left. It is unlikely this was the case given the timeline. (You can study this further by going to the links below the quesion mark (?) in the links section on this page.)

Banneker, now at home, continued to work on his Farmer's Almanac. He worked on an ephemeris* (ih-FEM-er-is) which is a chart showing the position of the sun, moon, and planets for each day of the year. He submitted it to publishers, but was unable to find anyone who would publish it.

In addition to submitting it to publishers he also sent a copy of his almanac to Thomas Jefferson who was the Secretary of State. In the letter he appealed to Jefferson for African-Americans to be treated with equality.

In order to submit his manuscript to multiple publishers he had to hand copy the charts and manuscripts over and over again. There were no copying machines or scanners to make the work easier. His first almanac was printed in 1792 and was a great success. The next year it included copies of the correspondence between Banneker and Thomas Jefferson.

People who didn't have clocks would use the almanac to tell the time of day because the time for sunrise and sunset for each day of the year was listed.

He included stories and articles in the almanac. His 1797 edition included a caution to his readers about the dangers of smoking.

After his 7th almanac he did not publish another, but he still calculated an ephemeris for each year 1798-1802 simply because he derived pleasure from doing it.

Some people did not like the favorable attention he had been given and men came to his house and fired gunshots.

The Ellicotts bought his land and paid him in installments until his death. He spent his last days quietly studying the heavens, watching the bees work, and writing in his journal. When he died he was almost 75 years old.

After his death the items he had borrowed from George Ellicott; the telescope, books, instruments etc. were returned to him. A fire destroyed his cabin on the day he was buried. The fire destroyed his wooden clock and his manuscripts, symbols of his life's work.

People seemed to forget about Benjamin Banneker for about 150 years, then in the mid 1980's archeologists discovered the remains of his home and interest in his life was renewed.

This biography by Patsy Stevens, a retired teacher, was written August 13, 2010.

The facts in this story were taken from the book Benjamin Banneker: American Scientific Pioneer by Myra Weatherly. order

A frequent question:

A frequent question: