Henrietta

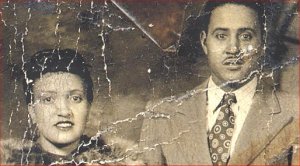

Henrietta Lacks and her husband Day had five children. Her family, descendants of slaves, was poor. In January 1951 she discovered a knot which she feared was cancer. She went to Johns Hopkins, a non-profit hospital in Baltimore, Maryland where a doctor took a biopsy of the growth to test it. It turned out to be a very aggressive type of cancer, and she was soon suffering through a series of treatments in an attempt to rid her body of it. But it continued to spread throughout her body. She lived about nine months and died on October 4, 1951. She was only thirty-one years old. Her five children, all very young, two still in diapers, were left motherless.After Henrietta's death, her husband Day had to work two jobs to support his family. Relatives came in to care for the children and another couple moved into the house to help. The woman, Ethel, was cruel to the children and they often went hungry. She put latches on the refrigerator and cupboards to keep them away from the food. They weren't allowed to have ice in their glasses because it "made noise." The children had to clean the house, do the laundry, and work in the fields. Ethel would beat them so badly they sometimes ended up in the hospital. They were finally moved to their big brother's home and life was better for them.

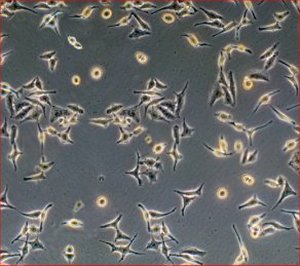

Immortal Cells

The tissue sample the doctors had taken during the surgery was sent to George Gey (rhymes with I) who was head of tissue research at Johns Hopkins. He had visited with Henrietta when she was in the hospital. George and his wife had spent 30 years trying to find a cure for cancer. They put some of Henrietta's cells to grow in a culture.* Usually human cells will die after a period of time, but Henrietta's cancer cells, unlike the others did not die! They continued to grow and grow. George's wife Barbara said they were "spreading like crabgrass" because they doubled every 20 hours. George was quite sure he had grown the first human immortal cells, and shared some of them with other researchers.HeLa Cells

Though they didn't release Henrietta's name, they called her cells HeLa cells, using the first two letters of her first and last name. In 1953 a newspaper, the Minneapolis Star printed an article about the woman behind the HeLa cells, but they got the name wrong. Instead of Henrietta Lacks they called her Henrietta Lakes. Gey was opposed to even identifying the woman whose cells were used.Then Collier's publication referred to her as Helen L. Next she was reported to be Helen Lane and Helen Larson. Because of all the false names being published, her family had no idea her cells were being used.

HeLa Cells in Research

In 1951 there was an epidemic of polio,* a crippling disease that was striking many children. In 1952 Jonas Salk developed a vaccine against polio, but it would need to be cultured on a large scale. A HeLa factory was built in Tuskegee where black scientists were trained and produced 20,000 tubes of HeLa each week. That was about 6 trillion cells. It was the first-ever cell production factory and it had been started with one vial* of Henrietta's cells.When it became apparent they would not run out of cells for the testing of polio vaccine, they began shipping the cells to scientists who bought them for $10 a vial plus the fee to send them by Air Express.

HeLa cells were used to develop chemotherapy* to treat cancer. They were sent into space in 1960 when a Russian satellite was launched and then the U.S. put some vials of the cells in a satellite launch. Her cells became even more powerful in space and grew even faster.

Technology using HeLa cells have been used to grow cornea transplants to help treat blindness. It has been used in HIV research, in cloning of tissue, and in diagnosing genetic disorders.

Chester Southam began experimenting by injecting cancerous HeLa cells into people. He told them he was testing them for cancer, but they were developing cancer. Three young Jewish doctors, remembering the research the Nazi's had done on Jewish prisoners in World War 2, refused to give the injections without telling the patients they contained cancer cells. They feared for their own lives if they complied because of the Nuremberg Code which specified that voluntary consent was essential. Southam's license was revoked for a year.

Contamination

In 1966 a geneticist named Stanley Gartler discovered that HeLa cells had contaminated cultures in many laboratories. The cells were so strong and aggressive they could travel through the air and contaminate other cultures were growing in the lab. He dropped the bombshell* at a conference in Pennsylvania. The contamination which had been occurring for years had become worldwide and had caused a lot of research to be worthless. It involved millions of dollars.The Family Learns About the Cells

Bobbette, Henrietta's daughter-in-law, just by chance, learned from a friend's relative (who happened to work in cancer research) that Henrietta's cells were being used in research. Bobbette was livid. Henrietta had died 21 years before and no one had told the family anything about the research. When they heard the news, some of the family mistakenly thought Henriette herself was still alive.Researchers decided they might be able to solve the contamination problem and learn to use Henrietta's cells in new ways if they could get blood from her family to test. At first the family cooperated. Susan Hsu collected blood from Henrietta's husband Day (who was also a cousin), her sons Sonny and Lawrence, and her daughter Deborah. They were told they were being tested to see if Henrietta's disease was hereditary.* Then they asked Deborah to give more blood. She thought they were testing her for cancer. She feared getting cancer because her mother had died with it at such a young age. Victor McKusick (who was one of the first scientists to use Henrietta's name) told Deborah that her mother's cells had been used to make polio vaccine and in genetic research. When he told about the research and about the cells being sent up in space and used in atomic bomb testing, Deborah was scared, afraid her mother was feeling pain because of all the testing.

To Sue or Not to Sue

The Lacks brothers became interested in the cells when they read an article stating vials of the cells were sold for $25 each. Neither Johns Hopkins Hospital nor George Gey had profited from the cells, but some biotech companies had made millions of dollars by selling the HeLa cells for anywhere from $100 to $10,000 for a vial.The Lacks family struggled financially and could not even afford medical insurance. They frequently talked about suing Johns Hopkins Hospital or the pharmaceutical* companies and trying to get some benefit for their family. When it became clear they were not going to get any money, they worked to get recognition for their mother.

A man named John Moore who had cancer learned his doctor was using his cells and sold the rights to a patent for $3.5 million. Moore sued, but the judge threw out the case. Moore appealed the case and won, but then the California Supreme Court ruled against him saying when you leave tissue in the doctor's office, you have abandoned it and anyone can use it.

A distant relation named Cofield contacted the Lacks family saying he was a lawyer and he would represent them in an effort to copyright the name Henrietta Lacks. In fact he wasn't a lawyer at all, but had served prison terms for fraud. He was a con artist.

In Henrietta's day, and even today, it is legal for doctors and researchers to use blood samples and people's cells without their permission. If they want to gather cells specifically for research, they must get the consent of the patient.

The Book

Rebecca Skloot became interested in Henrietta's story when she was in high school. She thought the story needed to be told. Years later she would embark on a 10-year odyssey and grueling research to contact the family and write Henrietta's story. When she told him her plan to write the book, Roland Pattillo, a professor at Morehouse said, "Oh, child you have no idea what you're gettin' into."The family didn't want to talk to her. Black people who lived near Johns Hopkins Hospital were deathly afraid of the hospital because of stories they had heard about the hospital snatching black people from the streets and experimenting on them. Slave owners in years past told such stories to discourage their slaves from running away. There was some truth to the stories because there was some experimenting on slaves.

But the hospital, built in 1873 with $7 million donated by Johns Hopkins, had served the community well. It was a charity hospital where they treated the poor and indigent* of all races. Today it is one of the top medical schools in the country.

Skloot persisted and the book was published in 2009. At the time of the printing, more than 60,000 scientific articles had been published about the research with HeLa cells and more than 300 papers a month were still being written. Even 50 years after Henrietta's death the HeLa cells were still aggressive and still contaminating other cultures.

Honoring Henrietta

In 1996 the BBC made an hour-long documentary film The Way of All Flesh about Henrietta Lacks.Roland Pattilla holds a HeLa conference every year in Henrietta's honor. He and his wife purchased a tombstone for her grave. No one knows the exact spot, but her children know it is near her mother's grave. Even if they can't identify a certain place in the cemetery, they know her cells continue to live. And they know their mother is very important in the medical field.

This biography by Patsy Stevens, a retired teacher, was written February 1, 2013.

References:

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot Order

A frequent question:

A frequent question: