The Meitner children were taught to listen to their parents, but to think for themselves.

Her formal schooling as a child ended when she was fourteen years old, but she still wanted to learn. She asked her father if she could study at the University of Vienna. However, the classes there were closed to women and Jews. She, being a woman from a Jewish family, was excluded. Her parents insisted she first learn how to be a teacher before she pursued a higher education. They felt she needed to have some way to support herself financially.

Though Jewish, Meitner converted to Protestantism when she became an adult along with some of the other members of her family.

In 1899 the university began to admit women even if they lacked a high school diploma. She began to prepare for the entrance exam which was called the Matura. She finished an eight year study in two years. She took the exam and passed. Fourteen women took the test and only four passed. Meitner was one of them. She was able to enroll and attend physics* classes with the men. She was 23 years old. Five years later she had a PhD in Physics.

She went to the University of Berlin where she, as a woman, was not allowed to use the same lab as the men for her experiments.

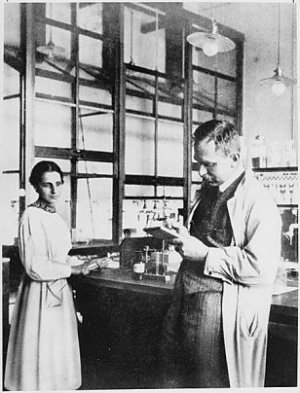

While in Berlin she worked with Otto Hahn. She and Hahn discovered a radioactive* element and named it protactinium.* She did most of the work because Otto had to serve in World War 1. Hahn, however, received all the credit for the work. She asked him repeatedly to give her the recognition due her, but it never happened.

Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn

In 1944 Hahn would receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the interpretation of nuclear* fission.* Meitner was not mentioned. Some say this was the greatest oversight ever made by the Nobel prize committee.

She stayed in Berlin as long as she dared, but fled the Nazis because they were about to arrest her. After 30 years in Berlin she went to Sweden.

Sometimes she would write scientific articles and just sign them "L. Meitner". The publisher thought she was a man. When he learned "L. Meitner" was a woman, he quit publishing her articles.

She had named the process on which she was working nuclear fission. Without her knowledge other scientists built on her work and called it the "Manhattan Project" which was actually the development of the atomic bomb. She refused to help with the development of the weapon. Meitner did not know the end result of her discovery would lead to weapons of mass destruction. She wanted her discoveries to be used for peaceful purposes. To her dismay, her research resulted in the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan to bring about the end of World War 2.

During her 60 years of work in the field of atomic physics she wrote 128 articles, served on scientific commissions, and served on the United Nations committee on atomic energy.

For many years she worked with her nephew, Otto Robert Frisch who was 34 years younger.

She and Eleanor Roosevelt in 1945 pledged to work together for world peace.

Albert Einstein affectionately called her "our German Madame Curie".

Two years before she died she received the Enrico Fermi* Award along with her co-workers Strassman and Hahn. In 1997, twenty-nine years after her death, the chemical element 109, the heaviest known element was named Meitnerium* in her honor.

On her gravestone is written "A physicist who never lost her humanity".

This biography by Patsy Stevens, a retired teacher, was written in 2008.

Many of the facts in this story were found in the book Lise Meitner and the Dawn of the Nuclear Age by Patricia Rife

A frequent question:

A frequent question: