He was born in Dunbar, Scotland, and as a boy enjoyed exploring the coast by the North Sea near his home. He started school when he was three years old. His grandfather had already taught him the alphabet by pointing out the letters on shop signs as they walked around town.

He began practicing for his mountain climbing adventures by climbing up on the roof of their house and daring his brother to do the same.

He says his father made him memorize scripture. He writes, "...by the time I was eleven years of age I had about three fourths of the Old Testament and all of the New by heart and by sore flesh".

(My Boyhood and My Youth - Chapter 1)

Boyhood sports included playing with gunpowder, climbing trees, and scaling garden-walls.

He was exceedingly interested in the stories in his readers about Audubon and his study of birds, and of lessons describing American forests.

One night his father announced the family was going to America. Father took only Sarah, John, and his brother David whose ages were 13, 11, and 9. He left the three youngest children and their mother in Scotland. They were to come later after he had a place for the family to settle. The voyage took six weeks and three days.

Father found some farmland in Wisconsin. John was utterly happy in this wilderness setting. Then the hard work began of clearing the land and building a house so they could send for Mother and the younger siblings.

Finally the house was finished, and Mother and the young ones joined them in Wisconsin.

Father had promised the boys a pony, and bought them a little two-year-old Indian pony which they learned to ride. Now they could roam even further.

Father wanted the boys to learn how to swim. He told them to observe how the frogs swam, and to do likewise. Once John nearly drowned when he panicked in the water. He later went by himself in a boat out to the deep water and dove off several times and swam back to the boat in order to overcome his fear.

Within a few years the land around them was settled almost every quarter section with home-seekers from Great Britain. Some of the people died of consumption* (tuberculosis), and some of plague or accident, but John's family remained intact.

John as a twelve-year-old boy ploughed the ground like a man, and it was also his job to dig out the remaining tree stumps to make way for the McCormick reaper after it replaced hand harvesting.

He also had to split rails to make long lines of fencing. He and his brothers and sisters worked seventeen-hour days. He continued working in the fields even while he had the mumps. Only once was he allowed to leave the field and stay in bed - when he had pneumonia. What a hard life for a child!

After the original farm was all cleared and the house was built, Father bought another farm; a half section of wild land, and they started all over again.

Once when John was not yet 20 years old he was digging a 90-foot water well by hand. When he had dug down about 80 feet he almost died when poisonous gas accumulated in the well. After he recovered and they found a way to stir the air in the hole, he was lowered again and chipped away until he struck water at 90 feet.

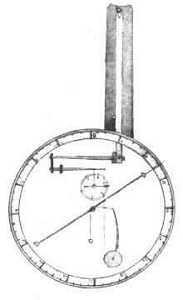

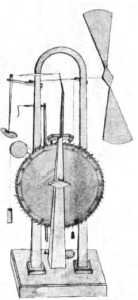

His father insisted John go to bed when everyone else in the family retired, but he gave him permission to get up early if he wanted to. He began waking up at 1 AM each morning, and he used this precious time to invent such things as clocks, thermometers, and barometers,* whittling* the parts out of wood. His neighbor encouraged him to display them at the State Fair.

Thermometer

Barometer

Though he had slaved for his father for years, Father would not promise him any financial help when John was ready to leave home. He left with $15 in his pocket and his father's advice, "Depend entirely on yourself".

He rode the train to Madison, Wisconsin, made his way to the State Fair and displayed his inventions. People were fascinated. He won a prize and a diploma. An article about him appeared in the Eastern newspapers. His father had never praised him for anything while he was growing up for fear of filling him with a sinful pride. Concerning the newspaper article John wrote, "I was afraid to read those kind newspaper notices, and never clipped out or preserved any of them, just glanced at them and turned away my eyes from beholding vanity".

He later said those early inventions opened many doors for him for years to come.

He went to State University for four years. One winter he taught school during the day and attended the University at night. He did not receive a diploma because he didn't pursue one course of study. He would pick and choose the courses he thought would be most useful to him.

In 1867 he had a terrible accident. The point of a file pierced his eye and he lost his sight in that eye. Then the other eye went dark for a period of months. When his sight returned he determined to spend the rest of his life looking at the beauties of nature.

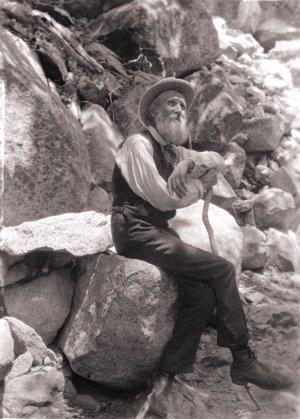

And that he did. He trekked on foot for hundreds of miles and once made a thousand-mile trek* to Florida. He traversed* the country and spent a lot of time in Yosemite. He traveled several times to Alaska.

He later would persuade President Theodore Roosevelt to set aside 148 million acres of land to be preserved as forestland and national parks.

He married Louisa (Louie) Strentzel, a woman from Texas, and moved to Martinez, California. He was forty-two years old and she was nine years younger. They had two daughters, Wanda and Helen, and he became quite wealthy.

In 1892 he created and became president of the Sierra Club. Its purpose was to preserve and open up a way into the Sierra Nevada mountains. In 1901 he led a group of 97 members of the club on a month-long exploring expedition. The group included his two daughters. He then began to hold the outings every year.

He died of pneumonia in 1914 at the age of sixty-six.

Muir's work lives on in today's ecology and environmental movements.

This biography by Patsy Stevens, a retired teacher, was written in 2007.

Many of the facts in this story were taken from Muir's writing

The Story of My Boyhood and Youth

(public domain, 1913, full view)

The boyhood of a naturalist: by John Muir

selected chapters from the book above (public domain, 1913, full view)

A frequent question:

A frequent question: