The year was 1761. The schooner,* the Phillis, was about to leave Africa.

The captain, Captain Gwinn had ordered that no children should be on his ship. However, among the captives being taken aboard there was a small African girl who had been kidnapped from her family. The nameless child was dressed only in a soiled piece of carpet. The ship was not as crowded as some slave ships. It only carried 70-80 captives. Some of the slave ships carrying 140-160 bodies were packed so tightly the people could not move. Still, conditions on the ship were horrible.

(Description of a slave ship)

When the ship arrived in Boston, Susanna Wheatley went aboard to pick out a slave to help her. She had planned to buy a woman slave, but she took pity on the poor little waif* who was about seven years old and bought her instead. She named her "Phillis" after the name of the ship which had brought her to America. The Wheatley family was wealthy and lived in a mansion on a busy street in Boston.

Phillis was treated well. In fact she was not treated like a slave at all. The family treated her like a member of the family. She ate at the table with them, had her own room in the attic, and did not have to do the chores the other slaves were required to do.

The Wheatleys did not let her associate with the other slave children, but she did have one friend, a fellow slave girl named Obour Tanner.

Obour had also been bought by a kind family who treated her well.

She attended church with her owners at the Old South Meeting House in Boston and was baptized in 1771.

John and Susanna had 18-year-old twins, Nathaniel and Mary. The family saw that Phillis was a bright intelligent child and Mary became her tutor. She taught Phillis to read and schooled her in geography, astronomy, history, the Bible, and classic literature. She even taught her Latin and Phillis could read books written in Latin. It was as if Mary had taken a precious jewel and polished it until it shone brightly. In time the slave girl became possibly the most educated woman in Boston.

Her mistress provided her with feather quills,* ink, and paper. She learned to write and would correspond with people, even famous people of the day.

Phillis became a poet. She wrote poetry about events that were happening. We learn about the days of the American Revolution from her writings.

She wrote poems about important people and their deeds.

She wrote a poem called To His Excellency General Washington

and sent the general a copy of it. He referred to her as a "poetical genius". Four months later she received an invitation from General George Washington to come for a visit. They met for about thirty minutes. Washington's secretary sent the letter to the Virginia

Gazette and it was published in the newspaper on March 20, 1776.

Susanna Wheatley encouraged Phillis in her writing and arranged for her to meet influential* people. She met John Hancock and Benjamin Franklin. Some of these people gave her books and some invited her into their homes. She visited and ate a meal with the Fitch family who owned the ship, the Phillis, on which she had come to America. On some occasions Phillis asked to be seated at a separate table from her host.

Susanna could not get Phillis's poems published in America, so when her poems began to be read in England, she sought a way to have them published there. The English were skeptical that such poetry could have been written by a slave. To authenticate* her work, she appeared before a group of eighteen American "judges" who questioned her until they were convinced she indeed was the author of the writings. They wrote a letter and sent it to England to vouch* for her works.

The books were printed and after a few months Phillis received 300 copies of her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. She, with the help of her friends, sold copies of it to people in the New England colonies.

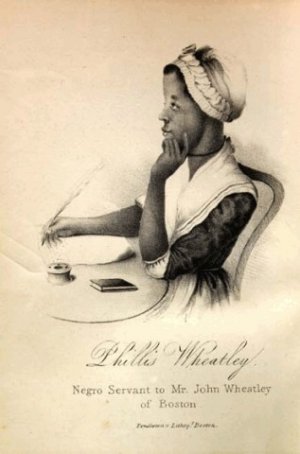

There was an engraving of a painting of Phillis in the front of the book. It is believed that a black slave named Scipio Moorehead painted the picture from which the engraving was made. The book was dedicated to the Countess of Huntingdon in England who helped to fund the publication.

Phillis was able to travel to England in an attempt to improve her health. She suffered with tuberculosis or asthma. While in England she was able to meet her admirers.

Unfortunately, Susanna became very ill while Phillis was away, and the girl had to return to care for her mistress. By cutting her trip short she was not able to visit with the Countess who had aided her.

Some of the people in England wondered how the Wheatleys could keep such a gifted person enslaved. Upon her return to America the family granted her freedom.

Phillis tried to sell subscriptions for a second printing of a book of thirty-three poems and thirteen letters, but she was unable to raise the money and the book was not printed during her lifetime.

After the Wheatleys died she no longer had anyone to depend on for support, and very shortly married another freed slave, John Peters. They had three children, but each child lived only a short time.

At first they had money to live well, but then hard times came.

Late in 1784 John was put in debtors' prison because he couldn't pay his debts.

Phillis's life ended sadly. She was working as a maid in a boardinghouse and lived in a dirty little room with her child. Phillis died December 12, 1784 at the age of thirty-one, and her child died a few hours afterward. They were buried side by side.

John, her husband put notices in Boston newspapers and collected her works, saying he was going to publish them. He didn't, but he did sell them to Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia. This was a fortunate turn of events because Dr. Rush made sure these manuscripts* were preserved for future generations. Much of her work has been lost or is in private collections and not available to the public.

The place of Phillis Wheatley's burial is unknown, but many monuments and public buildings have been named for her.

One of her best-remembered poems was On Being Brought From Africa to America

In her poetic eulogy to General David Wooster, she wrote:

But how presumptuous shall we hope to find

Divine acceptance with the Almighty mind

While yet o deed ungenerous they disgrace

And hold in bondage Afric's blameless race

Let virtue reign and then accord our prayers

Be victory ours and generous freedom theirs.

This biography by Patsy Stevens, a retired teacher, was written in 2011.

The facts in this story were found in the following books:

Phillis Wheatley: Legendary African-American Poet

by Cynthia Salisbury

Order

here

Phillis Sings Out Freedom: The Story of George Washington and Phillis Wheatley(selected pages) Order here

Phillis Wheatley: She Loved Wordsby Sneed B. Collard (selected pages) Order here

Phillis Wheatley: Slave and Poet by Robin S. Doak (selected pages) Order here

Hang a Thousand Trees with Ribbons: The Story of Phillis Wheatley by Ann Rinaldi (selected pages) Order here

A frequent question:

A frequent question: